The Consent of the Governed: Country Studies — Islamic Republic of Iran

Iran Country Study

Rankings in Freedom in the World 2016. Status: Not Free. Freedom Ranking: 6; Political Rights: 6; Civil Liberties: 6.

Iran |

Summary

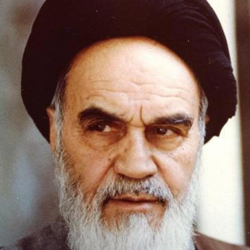

The territory of Iran, previously known as Persia, was ruled by monarchical dynasties or occupied and dominated by foreign powers for nearly all of its recorded history dating to classical times. There were only brief periods in the 20th century during which there was some measure of parliamentary democracy. In 1979, a revolution against the repressive regime of Shah Pahlevi, inspired by the exiled cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, resulted in the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran and a theocratic government. Since then, Iran’s clerical rulers have maintained a strong grip on the country's politics, economy, society, and culture. Pro-democracy movements that emerged in the late 1990s and in 2009 were suppressed by force and repression. Today, dissidents oppose the regime and its policies at risk of their life and freedom. In the 2013 presidential elections, the cleric and lawyer Hassan Rouhani, the regime’s former negotiator regarding its nuclear program and considered a moderate for advocating better relations with the West, won a large victory over other harder-line candidates.

Iran is the 17th-largest country in the world by area (slightly smaller than Alaska) and 18th largest by population (approximately 79 million people in 2015). It borders seven countries (Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Iraq, Pakistan, Turkey, and Turkmenistan) and three bodies of water (the Caspian Sea to the north and the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman to the south). The economy is dominated by oil: Iran possesses the world's fourth-largest oil reserves. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Iran ranked 29th in the world in 2014 in total GDP in nominal measurements (at about $440 billion). In per capita GDP, however, Iran ranked much worse, indicating wide disparities in Iran’s distribution of wealth: 93rd in nominal GNI (gross national income) per capita in 2015 ($5,048 a year). Poverty and unemployment rates remain in double digits.

Iran’s growth rates and economic conditions worsened over the previous decade due to a severe sanctions regime, including bans on oil sales, imposed by the United Nations to deter Iran’s development of nuclear weapons. After prolonged U.N.-authorized negotiations with the P5+1 group (the 5 members of the Security Council and Germany), Iran agreed in July 2015 to restrict its nuclear program to peaceful purposes for fifteen years in exchange for relief from international sanctions, including on significant frozen assets held in international banks.

History

Cyrus the Great

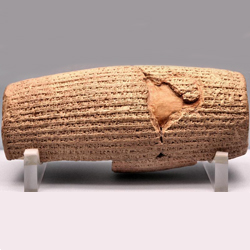

The Iranian state dates back to Cyrus II, who united several kingdoms into the Persian Empire in 550 BC. Known as Cyrus the Great, he also conquered most of the Middle East and Asia Minor to form the world’s first extended empire. Uniquely for that time, Cyrus instituted a policy of religious tolerance, which included ordering the return of Jews held in captivity in Babylon. He also issued the Cylinder of Cyrus, which lists allowances and freedoms that Cyrus granted to nations under his rule, including the right to reject his rule altogether. To show the Cylinder’s historical importance as the earliest known example of limited rule and tolerance of local religions and customs, the United Nations displays a replica inscribed on its headquarters building in New York City.

Cyrus Cylinder |

From Alexander to the Qajars

Cyrus's Achaemenid dynasty fell to Alexander the Great in 330 BC. After Alexander's death, one of his generals founded the new Seleucid dynasty, which controlled much of present-day Iran. Seleucid rule was followed by two long-lasting Persian dynasties, the Parthian (247 BC–AD 224) and the Sassanid (AD 224–642). Muslim Arabs invaded in 636 and largely subdued Persia by 650, converting it to Islam. Thereafter, the country was ruled by a series of Arab and Turkic dynasties, until being conquered in the 13th century by the Mongol leader Genghis Khan, whose dominion stretched from China. After more than two centuries of Mongol and Turkic rule, the Safavid dynasty was established in northwestern Iran in 1502, which declared Shiite Islam as the official religion. Iran today remains predominantly Shiite. The Safavid dynasty fell in the early 19th century, ultimately succeeded by the Qajar dynasty.

The Constitutional Revolution

The country’s history of empires and dynasties was interrupted at the beginning of the 20th century by the Constitutional Revolution of 1905–06, which established Iran's first elected parliament and a constitutional monarchy. The Qajar shahs, however, resisted parliamentary government and drew on Russian and British influence to limit constitutional rule. The 1907 Anglo-Russian Agreement delineated respective spheres of control in Iran’s south and north to Britain and Russia, with a "neutral" area in the center. In the south, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company was established by agreement with Shah Qajar to extract energy resources near the Persian Gulf. The efforts of Constitutionalists to defend the parliament’s powers were hampered by World War I, which saw increased Russian and British military presence. Iran’s parliament again asserted its powers after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, which weakened Russia’s imperial influence, and also later successfully rejected Britain’s attempt gain greater control over the country.

The Restoration of the Shahs—and Their Final Fall

A young army officer named Reza Khan organized a coup in 1921 and four years later he had the parliament officially depose the now largely powerless Qajar dynasty and declare him the new monarch under the name Reza Shah Pahlevi. Over the following years, he introduced a number of reforms in an effort to modernize Iran, while at the same time maintaining a heavy repressive hand to stifle internal dissent. The Shah’s refusal to help the Allies in World War II led Great Britain and the Soviet Union to invade the country, now formally named Iran, in 1941. The occupiers forced Reza Shah to abdicate in favor of his son, Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlevi.

Under pressure from the United States, allied troops withdrew from the country by 1946, after which parliament again reasserted its powers. In 1951, the parliament voted to nationalize the oil industry, which would have ended the British role in the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. A nationalist proponent of the plan, Muhammad Mossadegh, became prime minister despite opposition by the shah, who was forced into temporary exile. In 1953, monarchists and military officers, with support from the United States and Britain, returned the shah from exile to oust Mossadegh. The shah re-established full control over the state and signed an agreement for a joint British, Dutch, French, and US oil consortium to develop Iran's reserves.

Under Shah Pahlevi’s rule, Iran began a period of modernization, which included land reform and improving women’s rights. Measures to open the country, however, were accompanied by a system of increasing political repression and torture carried out by the notorious SAVAK secret police forces. Repression and growing economic inequality created greater and greater resentment within the population and ultimately led to a popular revolution in early 1979 that resulted in the creation of the Islamic Republic.

Consent of the Governed

For most of its history, Iran was governed by either foreign empires or hereditary dynasties exercising absolute control. The Constitutional Revolution of 1905–06 was thwarted by foreign interference and the re-establishment of monarchical rule in 1924. Following World War II, the nationalist government led by Prime Minister Muhammad Mossadegh was ousted in 1953 by Shah Pahlevi, backed by the US and the United Kingdom. There was secular opposition to the Shah’s rule, but the Islamic movement led by an exiled cleric, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, also gained strength as the Shah’s modernization campaign failed to improve the economy and became associated with inequality, corruption, and harsh repression. Joint secular and religious opposition protests caused Shah Pahlevi to flee the country in January 1979. In early February, Ayatollah Khomeini, returned from Paris and was greeted by a cheering crowd of two to three million. He quickly established an interim government that supplanted a caretaker regime. He then called for a quick plebiscite to establish an Islamic Republic without debate over the content of the constitution or established democratic procedures to ensure a fair plebiscite. An authoritarian theocracy, a state ruled by religious leaders, quickly replaced the secular authoritarian regime.

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini |

The Islamic Republic

The plebiscite approved an interim constitution based on the principle of velayat-e faqih (guardianship by the Islamic jurist). Ayatollah Khomeini became Supreme Leader and cemented theocratic rule through amendments to the constitution that effectively prevent the people from changing their government or constitution. Formally, there is a division of government into executive, legislative, and judicial branches, with general elections for president and a parliament (called the Majlis), which are staggered every four years. All branches of government, however, are effectively overseen by the Supreme Leader, a high cleric selected by an Assembly of Experts made up only of high clerics.

The Supreme Leader

The constitution’s establishment of theocracy is complete. For one, the Supreme Leader is granted the power to appoint the heads of the key levers of power: the military, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), the chief of the judiciary, and the head of state television and radio. The Supreme Leader also controls the appointment of the Guardian Council, which is tasked with vetting political candidates for all elected offices and reviewing legislation passed by the parliament. In 1988, Ayatollah Khomeini created another body, the Council of Expediency, fully appointed by the Supreme Leader, with power to resolve disputes between the parliament and the Guardian Council. While the constitution formally establishes some separation of constitutional responsibilities for running the government, in practice the Supreme Leader has supervisory powers over all parts of government. During his rule, Khomeini exercised enormous influence. He forced out the initial secular prime minister and immediately set Iran on an anti-Western course by encouraging the takeover of the US embassy in 1979 and deliberately encouraging a deep paranoia of Western, and particularly US, influence. He imposed a strict set of Islamic laws that banned informal contact between unrelated men and women, forced women to cover their heads and bodies in public, among many other restrictions.

The constitution stipulated that after Khomeini died, a new supreme leader would be chosen by the Assembly of Experts. This is a body of senior clerics supposedly “elected” by popular vote in staggered terms of eight years. In practice, there is no real choice since all candidates for the Assembly are vetted by the Guardian Council. (In 2015, even Khomeini’s grandson, an imam reported to have more moderate views, was blocked from running for the Assembly of Experts.) Upon Khomeini's death in 1989, the Assembly appointed Ayatollah Ali Khamenei as supreme leader. While the Assembly of Experts has the responsibility to review the Supreme Leader’s actions and retains the formal power to recall him if he violates the constitution, the Supreme Leader’s overall powers to control the membership of both the Guardian Council (and thus the Assembly of Experts), negates the formal power to change leaders.

A Reform Movement Is Thwarted

In the mid-1990s, a reformist movement arose around student protests and propelled the election of Mohammad Khatami in 1997. While approved by the Guardian Council, he had campaigned as a moderate for president against harder-line backers of theocratic rule. Using their limited powers, Khatami and his allies in parliament took steps to liberalize the media, encourage the expression of opinion, allow use of the internet, free up parts of the economy, and even ease enforcement of Islamic social controls. Reformist parties supporting Khatami won some 80 percent of the vote in the 1999 municipal elections and about two-thirds of the seats in the Majlis in the 2000 elections. In 2001, Khatami won reelection as president with nearly 80 percent of the vote.

The regime’s theocratic institutions, however, began to re-assert their power at the direction of the Supreme Leader. The Supreme Religious Council and the Expediency Council vetoed legislation and counteract reforms through decrees. For the 2004 parliamentary elections, the Guardian Council struck 2,000 reformist candidates from the electoral list for parliament for violating “principles of sovereignty and national unity” or “questioning the Islamic basis of the Republic.” After regaining control over the Majlis, the theocratic leadership then ensured the election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, previously the mayor of Tehran and considered a hardline supporter of the Iranian Revolution, in the 2005 presidential elections. Vote rigging ensured the defeat of a relatively moderate cleric, former President Rafsanjani.

The Ministry of Security, directly responsible to the Supreme Leader, carried out increasingly repressive policies, ordering the closure of reformist media, non-governmental organizations, and political parties and arresting outspoken journalists, human rights lawyers, and students. Independent trade union leaders were imprisoned after organizing strikes against the government’s economic and wage policies. At the same time, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), the most important vehicle for consolidating the revolutionary regime in 1979–81, resumed its role as the regime’s ultimate enforcer. It aggressively sought out violators of Islamic proscriptions and national security laws. Anyone arrested by the IRGC is tried before its revolutionary tribunals, not the civil courts, and so has no rights to due process. The IRGC targeted women through enforcement of Islamic restrictions on movement, attire, social contact, and political representation. Students were arrested for minor religious infractions, such as allegedly violating fasting rules during the Islamic holy month of Ramadan. Three prominent Iranian Americans were arrested for conspiring to foment revolution, part of a campaign to “root out foreign influences.” Although the three were later released after an international campaign, dual citizens have continued to face arrest and charges of treason.

Civil society and cultural and human rights activists continued to organize opposition to the government’s policies. This was symbolized by the efforts of human rights lawyer Shirin Ebadi. Her non-violent advocacy for women’s and human rights had earned her the 2003 Nobel Peace Prize (see link to her Nobel Lecture in Resources). She used the resulting international recognition to further her work, but in the face of death threats she went into exile in 2009 and currently lives in London.

A Second Revolution Is Crushed

Ahmadinejad campaigned on populist promises to redistribute oil revenues to the poor through subsidies and reduced-rate loans, but these pledges went largely unfilled. His focus as president was to foster Iran’s nuclear weapons program, harden a confrontational stance towards the West, and call for the destruction of Israel. Despite the threat of sanctions, Iran continued to refuse cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to monitor its nuclear program to ensure it was not being used to develop nuclear weapons — as was widely suspected and later confirmed by the IAEA. In 2006, following a report by the IAEA detailing Iran’s lack of cooperation and its likely development of nuclear weapons, the United Nations initiated sanctions on Iran that increased in severity over the next years. In the 2009 presidential elections, the Guardian Council approved three candidates to challenge Ahmadinejad, who appeared to be still favored by the theocratic leadership. Mir Hossein Mousavi, a former prime minister, campaigned as a reformer and emerged as the main challenger by confronting Ahmadinejad in televised debates. Mousavi gained wide public support as a result but the regime brooked no possibility of defeat. Immediately after polls closed the government-controlled media announced Ahmadinejad as the winner with nearly 70 percent of the vote against Mousavi’s 28 percent. The regime’s blatant fraud prompted huge protests involving hundreds of thousands of people demanding democratic change. Organized in part through widespread use of cell phones and social media, the protest movement (called the Green Revolution) lasted for months, but eventually dissipated in the face of pervasive police repression. Protests were dispersed by force and at least 72 people were killed. Mousavi, his wife, herself a prominent intellectual, and Mehdi Karroubi, a fellow reformist candidate who had thrown his support to Mousavi, were placed under house arrest (where they have remained).

Current Issues

In response to the 2009 protests, Green Revolution leaders and hundreds of other activists were imprisoned, non-governmental organizations were closed, and students who participated in the protests were expelled from universities. In addition to holding hundreds of political prisoners, the government has continued to imprison thousands of people on charges of committing religious crimes such as moharebeh (“enmity against God”). Revolutionary Tribunals sentence people not only to harsh prison terms but also to severe floggings (up to 100 lashes) and, in many cases, execution, usually by public hangings. (Next to China, Iran has the second highest number of executions in the world — and the highest rate per capita.)

Presidential elections held in 2013 were considered significant for the election of Hassan Rouhani, who won 51 percent against seven candidates allowed to run by the Guardian Council (it excluded 600 other candidates). Rouhani, although he is considered close to Khamenei and served as the former chief negotiator in international negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program, pledged a reformist government that would adopt comparatively more liberal policies and attempt to ease strained relations with the West. Rouhani also signaled willingness to negotiate over Iran’s nuclear program, a change that appeared to be the result of the increasing economic impact on Iran of international sanctions, which now included strict bans on arms and oil sales, international bank transactions, and freezing of assets held by the IRGC, among others. President Barack Obama repeatedly stated the US’s position never to allow Iran to possess nuclear weapons, including by military means if necessary. However, President Obama had also made clear willingness to negotiate an agreement that prevented Iran from obtaining such weapons. In fact, Rouhani’s public position during and after the presidential campaign reflected initial behind-the-scenes discussions between the Obama administration and Iranian representatives aimed at such negotiations that began in 2011, as the harsher sanctions began to take hold.

Following a speech to the U.N. General Assembly in New York in September 2013, two months after his election, Rouhani engaged in a highly symbolic telephone call with President Obama. The call initiated the formal renewal of talks with the P5+1 group (the five U.N. Security Council members and Germany) on Iran’s nuclear program. After reaching an interim agreement, a final Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action was signed between Iran and the P5+1 group in July 2015 and its terms have been generally carried out. Under the agreement, Iran agreed to significantly reduce its levels of enriched uranium, mothball two-thirds of its centrifuges capable of enriching high-grade uranium and plutonium, incapacitate its plutonium reactor, and allow inspections of its nuclear facilities, although with notification, for a period of fifteen years. In exchange, the P5+1 agreed to the lifting of the international sanctions regime, including release of frozen international assets estimated at $100 billion and the eventual lifting of the arms sales embargo. The agreement was opposed by two key US allies in the region, Israel and Saudi Arabia, which fear that Iran will not ultimately abandon its nuclear weapons program and is just using the agreement to gain economic relief from sanctions. It also has been opposed by members of the US Congress. The IAEA, however, confirmed that Iran had carried out the terms of the deal by early January 2016, triggering the process to end international sanctions.

At the same time, the Iranian government released three dual US-Iranian citizens, including Washington Post reporter Jason Rezaian, who had been sentenced by Revolutionary Guards tribunals to harsh prison terms for “violating national security” or taking part in alleged foreign conspiracies. In exchange, the US released seven Iranian Americans sentenced to espionage and violating the international sanctions. The releases appeared to signal further easing of tensions with Iran, however the government has subsequently arrested other dual US-Iranian citizens, including a prominent energy contractor, and temporarily seized an American navy vessel and held its sailors under arms for entering Iranian waters.

Iran’s nuclear diplomacy did not otherwise alter Iran’s foreign policy. Since his inauguration, Rouhani has reiterated Iran’s hostility towards Israel, stating that the “the Zionist regime” was “a sore sitting on the Islamic world.” Similar statements are frequently issued by high-level officials and clerics. Iran has continued to finance, train and equip radical and terrorist groups like Hezbollah and Hamas, including its missile attacks on Israel in 2014, and to back Syria’s Assad regime, which is dominated by a fellow Shi’ite sect, against a popular uprising (see Country Studies of Israel and Syria). Iran has also continued ballistic missile tests up to a range of 2,000 since the agreement was signed, prompting some US lawmakers to call for imposing separate sanctions on potential delivery vehicles for weapons of mass destruction.

Internally, Rouhani took several modest initiatives to liberalize the economy and social life, at least compared to the previous administration. Soon after his inauguration, he eased some media and internet restrictions, released a dozen political prisoners, and urged the restoration of students who had been expelled from the university for political activity in 2012–13. He also expressed disapproval of arresting people for minor infractions of religious prohibitions, including the making of a video, “Happy in Teheran,” in which seven youths danced on a rooftop to the popular Pharell Williams song, “Happy” (see links in Resources). Nevertheless, a Revolutionary Tribunal court sentenced the seven youths to nine-months to one-year prison terms and 91 lashes, with sentences suspended so long as the youths did not engage in any additional “illicit relations” or violate other Islamic law.

Overall, Freedom House’s Surveys of Freedom in the World report that there is little change in respect for human rights and continues to rank Iran among the world’s “not free” countries. The Supreme Leader and the theocracy’s main institutions of control continue to exert dominant power. The Expediency Council has rejected several reform laws, while the Guardian Council rejected more than 6,000 candidates for parliamentary elections held in February 2016, including 3,000 candidates who were considered supporters of the limited reform course proposed by President Rouhani. In the end, only a minority of seats went to Rouhani supporters and a subsequent second-round re-affirmed the dominance of the religious hierarchy, similar to municipal elections. In one case, the Guardian Council declared that one independent woman candidate, Minoo Khaleghi, would be barred from parliament because pictures (that she claimed were false) showed her not wearing a head covering while traveling to Europe and China (see New York Times articles for recent events). The case established the assertion of new powers by the Guardian Council to vet not only candidates but also elected members of the Majlis, or parliament.

Hundreds of political prisoners remain in jails or under house arrest. At the public urging of the Supreme Leader in late 2015 and early 2016, the Revolutionary Guards stepped up arrests and prosecutions for threats against national security, questioning the theocratic basis of the Islamic Republic, and infractions of religious laws. Harsh sentences, including long terms of imprisonment and floggings, have been meted out by the Revolutionary Tribunals against poets, filmmakers, students, trade unionists, and others (see, e.g. reports of the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran and other links in Resources).

Despite a regime of comprehensive repression, Iran’s civic and pro-democracy movement continues to be active in both open and clandestine ways, aided often by Iranian exiles committed to bringing change to their country. For example, Democracy Web has been translated into Persian by the group Tavaana and is being used in its online courses involving hundreds of students inside Iran. While democracy advocates are unable to organize opposition freely, the 1997-2004 reformist movement and the 2009 protest movement showed that a large part of Iranian society supports liberalization and seeks an end to the current theocracy.